A Supply Chain Fiasco and the Inflation Outlook

Covid 19 has upset life on earth in many ways. The latest disruption is quite serious. Christmas in parts of the western world may go down the tubes. No Toys, no Turkeys, no Trees (of the X’mas kind) and no Toilet paper…WTF!

The economists have a term for it. Supply-chain fiascos.

This is not easy to explain to laymen. But we will try to do that in this commentary.

First of all, the causes of the supply chain problem are many. It arose out of a perfect storm. It is both short term causal factors as well as long term ones. One thing though. It is NOT a global supply chain crisis. There are no such problems, at least not to the same extent, of shortages of goods in other parts of the world. From media reports, it seems that the worse of these shortages are occurring in the US and the UK.

In the UK, it is mostly the after-effects of Brexit – a self-inflicted problem. No milk, no petrol, no bread, no pasta, no toys, no Christmas trees etc… What can we say? When a government is incapable of thinking through some very basic economics to implement a completely senseless policy, and the country cannot, over a five-year period, educate its population on what is good or bad about a proposed policy, everybody ends up paying for it. The supply chain problems in the UK will continue to recur as Brexit takes effect after Covid.

UK shot itself in the foot by leaving the EU, when it did not figure out how abandoning 50 years of economic integration with its continental neighbours would leave it vulnerable to disruptions in the supply of basic goods from across the English Channel. Not only that, the cutting off of immigrant labour just because there is xenophobia with no strategy to muster and train local workers to replace the Poles (among other East Europeans) leaves the trucking of goods into the UK or the slaughter of turkeys, etc mired in non-productivity. Where are those Englishmen who clamoured for the jobs they wanted back from the Poles?

In the US, the empty consumer shelves are not so different from the UK. In their turn, the Americans tried to shut down a long-term trading relationship with the Chinese. Trump’s tariffs, unchanged by Biden, have now caught up with the US economy. The tariffs did NOTHING to change the pattern of trade; they did not increase US exports to China and they certainly did not decrease the imports from China either. In fact, in 2021, the US trade deficit with China reached record highs. Every economist would have said to US policy makers, “I told you so…”

The insatiable demand for cheap but high-quality consumer goods in the US did not reduce imports from China, and led instead to the burden of the tariffs being borne by US consumers. The trade war backfired.

And it has gotten worse. The Covid pandemic led to changes in consumption patterns, for example WFH meant that new spending went into improving home working environments. Guess what, many of these types of consumer goods are made in China. Covid increased imports.

The talk at the beginning of the Trump tariff war was also for US companies to shift supply chains to Vietnam, India and other SEAsian countries, but after several years, none of these plans have panned out. It was not for lack of trying. Indeed, there were serious efforts which led to some of these substitute producing countries getting an influx of projects. But this is in fact contributing to the supply chain failures because Covid turned out to be much worse in those places than in China, and none of them could provide the comprehensive manufacturing base which made China successful in the first place. All the world got was more screws-up in the supply chain situation.

At this point in time, the supply chain problems in the UK and the US are all attributable to the attempt to reverse decades of open trade with a sudden organizational change thrust on parties that are not in any position to change. The result is a foul-up, occurring in the midst of rapidly changing demand patterns caused by Covid 19.

We can identify the following key reasons for the supply chain shortages:

- Insatiable demand for Chinese imports

The U.S. Census Bureau reported recently that the U.S. goods trade deficit reached a record of $915.8 billion in 2020, an increase of $51.5 billion (6.0%). The broader goods and services deficit reached $678.7 billion in 2020, an increase of $101.9 billion (17.7%). The U.S. goods trade deficit in 2020 was the largest on record, and the goods and services deficit was the largest since 2008.

The rapid growth of U.S. trade deficits reflects the combined effects of the COVID-19 crisis, which caused U.S. exports to fall by more ($217.7 billion) than imports ($166.2 billion), and by the persistent failure of U.S. trade and exchange rate policies over the past two decades. The single most important cause of large and growing trade deficits is persistent overvaluation of the U.S. dollar, which makes imports artificially cheap and U.S. exports less competitive.

The U.S. goods trade deficit is increasingly dominated by trade in manufactured products, as shown in the figure below. The manufacturing trade deficit reached record highs of $897.7 billion—98% of the total U.S. goods trade deficit—and 4.3% of U.S. GDP in 2020. Primarily due to these rapidly growing manufacturing trade deficits, the U.S. lost nearly 5 million manufacturing jobs and 91,000 manufacturing plants between 1997 and 2018 alone, and an additional 582,000 manufacturing jobs in 2020. In short, what the Americans buy, they have to import.

A significant percentage of those imports, 21.2 percent, come from China.

Growing U.S. goods trade deficits, 1997–2020

|

U.S. goods trade deficit |

Manufacturing trade deficit |

|

|

1997 |

$198.43 |

$130.69 |

|

1998 |

$248.22 |

$186.55 |

|

1999 |

$337.07 |

$259.03 |

|

2000 |

$446.78 |

$317.24 |

|

2001 |

$422.37 |

$304.11 |

|

2002 |

$475.25 |

$362.64 |

|

2003 |

$541.64 |

$403.09 |

|

2004 |

$664.77 |

$487.44 |

|

2005 |

$782.80 |

$541.40 |

|

2006 |

$837.29 |

$558.54 |

|

2007 |

$821.20 |

$532.08 |

|

2008 |

$832.49 |

$456.07 |

|

2009 |

$509.69 |

$319.29 |

|

2010 |

$648.67 |

$412.65 |

|

2011 |

$741.00 |

$440.55 |

|

2012 |

$741.12 |

$467.74 |

|

2013 |

$700.54 |

$458.81 |

|

2014 |

$749.92 |

$526.90 |

|

2015 |

$761.87 |

$629.78 |

|

2016 |

$749.80 |

$647.32 |

|

2017 |

$799.34 |

$695.52 |

|

2018 |

$880.30 |

$779.48 |

|

2019 |

$864.33 |

$793.36 |

|

2020 |

$915.80 |

$897.71 |

Source: EPI analysis of Census Bureau and the USITC trade data.

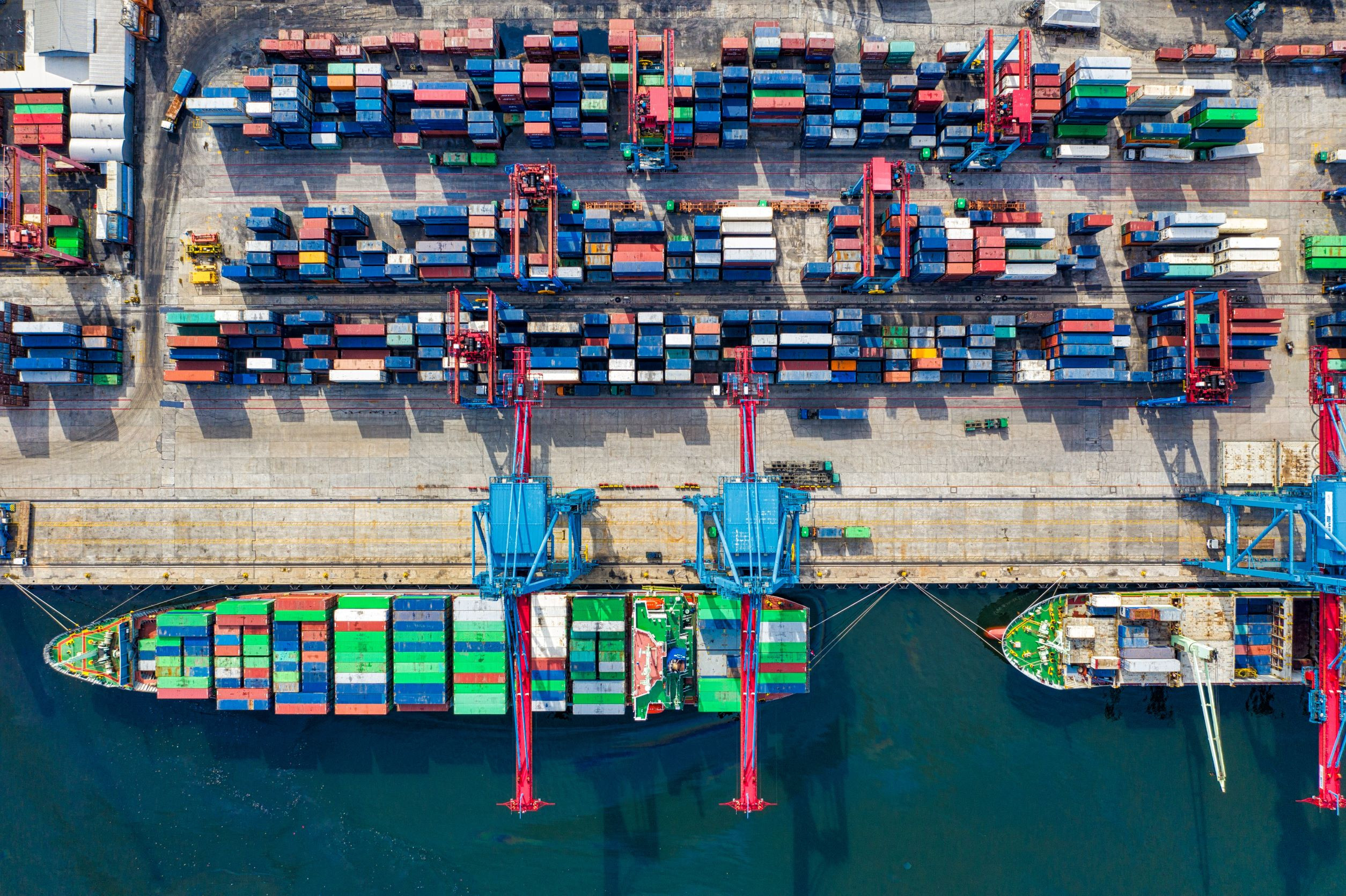

Growing trade deficits with China are a fundamental cause of the growing supply chain problems that the US is currently facing. When so much of its consumption comes from abroad, the supply chain is stretched out. The goods have to come from the East Coast of China to the West Coast of the US. Most of that stuff end up in Los Angeles/Long Beach port. Any log jam that occurs in that physical trade route will disrupt its flow. And obviously the more goods that go through that trade route is going to reach capacity at some point in time. There’s only so much stuff you can push into a pipe. When that happens, a “supply chain” breakdown occurs.

Growing U.S. trade deficits over the past two decades, which reached record levels in 2020, have decimated U.S. manufacturing. If there is a supply chain problem, domestic manufacturing cannot solve the problem. You cannot build a new factory, train the workers and source all the materials for making stuff, to replace imports that are not coming into the country overnight.

As a matter of fact, it is interesting to note that the US is trying to counter China in the Western Pacific using the excuse of Taiwan. The bulk of the trades routes that need to be protected come from China to the US, and this is getting bigger and bigger. It looks like shooting oneself in the foot again.

2. Changing demand patterns in a very short time.

Covid 19 was a game changer. When it happened and the world tried to copy the draconian lockdown methods of the Chinese, everybody got screwed up by the effort. It has been shown that no other country can be quite like China. Nobody can lock down entire cities (Wuhan, 9million people) and provinces (Hubei, 50 million people) like the Chinese did.

Even the most internet-connected countries in the world could not use Work From Home to overcome the economic effects of lockdown. And WFH has an indirect impact on consumption patterns. Factories were closed down, and businesses postponed orders and production to change their pattern of business in order to survive lockdowns. When this happened, changes in the mix of goods being brought into the US from China led to delays in the logistics. Over many months of changes, the backlogs grew.

As the New York Times recounted, “Americans took the money they used to spend on such experiences (such as vacations and dining out) and redirected it to goods for their homes, which were suddenly doubling as offices and classrooms. They put office chairs and new printers in their bedrooms, while adding gym equipment and video game consoles to their basements. They bought paint and lumber for projects that added space or made their existing confines more comfortable. They added mixers and blenders to their kitchens, as parents became short-order cooks for cooped-up children. The timing and quantity of consumer purchases swamped the system. Factories whose production tends to be fairly predictable ramped up to satisfy a surge of orders.”

3. Covid caused factory closings outside China

In the early days of the Trump trade war on China, many US companies complied with the call to reduce their dependence on Chinese manufacturing. They shifted some production facilities to Vietnam, India and other countries. As it turned out, these new supply centres were hit far worse than China by the pandemic. Many factories shut down or were forced to reduce production because workers were sick or in lockdown. In response, shipping companies cut their schedules in anticipation of a drop in demand for moving goods around the world.

Besides, many MNCs found that the work ethic in many of the new supply centres cannot match that in China. Other than Vietnam, which is quite similar in cultural characteristics to their neighbour in the north, other countries were not quite the same. Some countries had workers that would disappear if they were given monthly wages and would come back to work only after they have used up all their money. Weekly wages were found to be more persuasive to keep workers on the production lines. Quirky things like that did not make for a smooth diversification of the Chinese supply chain.

In short, MNCs found that there were strong reasons why China came to dominate the global supply chain, and there was no short-term replacement for that. To the extent that some of these supply chains were located in Covid-stricken countries outside China, they added to the woes of delayed production.

And even if there are no problems of new factories ramping up output to meet new demand, the surge in demand clogged the system for transporting raw materials to the factories that needed them. At the same time, finished products — many of them made in China — piled up in warehouses and at ports throughout Asia because of a paralysing shortage of shipping containers.

4. Missing Containers

These containers, according to the New York Times, “got stuck in the wrong places. In the first phase of the pandemic, as China shipped huge volumes of protective gear like masks and hospital gowns all over the world, containers were unloaded in places that generally do not send much product back to China — regions like West Africa and South Asia. In those places, empty containers piled up just as Chinese factories were producing a mighty surge of other goods destined for wealthy markets in North America and Europe.

Because containers were scarce and demand for shipping intense, the cost of moving cargo skyrocketed. Before the pandemic, sending a container from Shanghai to Los Angeles cost perhaps $2,000. By early 2021, the same journey was fetching as much as $25,000. And many containers were getting bumped off ships and forced to wait, adding to delays throughout the supply chain. Even huge companies like Target and Home Depot had to wait for weeks and even months to get their finished factory wares onto ships.

Meanwhile, at ports in North America and Europe, where containers were arriving, the heavy influx of ships overwhelmed the availability of docks. At ports like Los Angeles and Oakland, Calif., dozens of ships were forced to anchor out in the ocean for days before they could load and unload. At the same time, truck drivers and dockworkers were stuck in quarantine, reducing the availability of people to unload goods and further slowing the process. This situation was worsened by the shutdown of the Suez Canal after a giant container ship got stuck there, and then by the closings of major ports in China in response to new Covid-19 cases.

Many companies responded to initial shortages by ordering extra items, adding to the strains on the ports and filling up warehouses. With warehouses full, containers — suddenly serving as storage areas — piled up at ports. The result was the mother of all traffic jams.”

The log jam in the trans-Pacific transportation routes ended at Los Angeles/Longbeach port, the point of entry for the huge flow of goods from China into the US. And that’s where the crunch came. Due to the larger flows of goods into the country, and the changing pattern of goods, the system at Los Angeles/Longbeach basically broke down. The port workers were not working the number of hours that can clear the backlog of goods continuously coming in. Containers were stacked up wharf-side and ships could not berth to unload filled containers.

The pinhole that was Los Angeles/Long Beach port to send a torrent of goods into the country stayed that way – a pinhole - and even Presidential intervention by Biden did not help. The effort to get those port workers to work 24/7 over weekends were not received well. They liked their 5-day work-weeks and the rest of the country will just have to wait for their Christmas gifts stuck in containers and ships.

5. Land transport shortcoming

Even if goods can get out of the port area in the US, there is a huge shortage of trucks to then deliver the goods inland to the vast interior. How did this happen? It is result of a trucking industry caving in to the cost cutting pressures of the large companies, all acting to make more profits for themselves. Even truckers who own their own vehicles are not able to make a decent living and many are leaving the industry. It is estimated that the trucking industry is short of 100,000 drivers. The current problem is just a forerunner of things to come.

As it turns out, the problem in the US is not dissimilar to that in the UK. Truck driving is no longer a good way to make a living, and it is an activity that is increasingly pursued by poor immigrants who have no better way of earning money. Citizens don’t want these jobs, and when the US tightens border controls and the UK leaves the EU, the immigrants who would gladly do this kind of work can no longer be found. The system breaks down.

6. Infrastructure inadequacies

In the case of the US, it is abundantly clear that the transhipment system that is now in existence does not live up to the demands of the day. All of these are infrastructure. The US has the infrastructure of a third world country. Los Angeles/Long Beach port is operating on human labour, organized as unions. Compare this to Tianjin Port in China which is AI driven, and the port is apparently run by just about a dozen skilled workers.

The Federal Highway system on which goods are delivered from the West Coast to the inland cities used to be the envy of the world. It criss-crosses the nation from west to east and north to south, but its efficiency to deliver goods by truck at this time in human history cannot be said to be a marvel of engineering.

In its own continental sized country, China has both superhighways PLUS a network of high speed rail PLUS numerous airports for all its cities, big and small. This has led to the development of a system of logistics that is probably the best and cheapest in the world. You can buy cheap agricultural products from some remote farm halfway across the country and you can get it the same or next day at a cost of delivery that is almost negligible, making no difference to the cost of fruits or vegetables that are dirt cheap in the first place. It is amazing.

That is why China is able to deliver as a manufacturing hub that can make anything because its factories can source for everything within the country. Manufacturing supremacy did not come about because they have factories making stuff; they also have a superlative logistics system that moves stuff, from raw materials to components to final goods around the country, enabling regional comparative advantages to be maximised.

In time, the global supply chain will recover. Covid will be suppressed eventually by vaccinations and the mother of all traffic jams will be resolved. But the current crisis has revealed a number of serious problems in the way global manufacturing has been organized for the last two generations. One is a management principle called Just in Time inventory, which actually means no inventories. Factories are organized to have all their suppliers bring their components “just in time” to be used in the production, and therefore, the main factory such as a car manufacturer, does not need inventories of these supplies. Hence no warehouses. This has led to costs of production being squeezed to the bone. All inventory costs have been purged and this is one of the factors that has basically led to the lack of inflation in manufactured goods over the past few decades.

This is likely to change. The current shortages due to the mother of traffic jams will be transient and the accompanying inflation may be, as the Fed and the Treasury believe, transitory.

But it will not be the case if the MNCs try to plug the deficiencies revealed in the crisis. For example, if manufacturers relax Just in Time inventory policy and start to incur costs in warehousing and spare parts, the final products will have to increase in price. The long era of manufactured goods also dropping in price or getting better in quality for the same price may be over.

Wai Cheong

Investment Committee

The writer has been in financial services for more than forty years. He graduated with First Class Honours in Economics and Statistics, winning a prize in 1976 for being top student for the whole university in his year. He also holds an MBA with Honors from the University of Chicago. He is a Chartered Financial Analyst.